8: The Black Death, Capitalism and Societal Transformation

14/04/25

The one thing almost everybody (that is, almost everybody who accepts civilisation as we know it is in big trouble) agrees with, it is that capitalism is somehow right at the heart of all of it, and that whatever the new paradigm is, it cannot include capitalism. I wonder whether the reason everybody can agree about this is that everybody means something different when they use the word “capitalism". I think capitalism might be the wrong target. It is too nebulous and vague, and nobody appears to be able to imagine a realistic alternative. A better target is “growth-based economics”, because this would challenge the capitalists to either dream up a post-growth version of capitalism (can it be done?) or be forced to agree that capitalism has to go. I had been thinking about this when I noticed this in the first Second Renaissance Whitepaper:

"There are no clean switches between paradigms - and indeed one paradigm

may be ‘peaking’ within a given culture even as another is beginning.

Importantly, this means that whatever comes next, we can be sure, is already

nascent around us, in its best and its more harmful aspects. However, it’s

impossible for us to know what it will become - and much has yet to be

determined. Our task as conscious ancestors of a Second Renaissance lies in

sensitivity and imagination. We may feel around us in the dark for clues as to

the features our next paradigm may already possess. What fresh modes of art

and social organisation are emerging right now, what values do they embody,

and which do we want to amplify? We may examine our current foundations,

asking what alternative views and values might allow us to rebuild on a more

sustainable base. And we may radically enlarge our imagination regarding the

kind of future society we might want to see without dismissing any hopes as

unrealistic. After all if nothing else, we know that humanity is capable of

surprising itself. Could a citizen of mediaeval Europe have dared to hope for

the shifts in quality of life and relative social equality that lay ahead?"

The rest of this post is based mainly on David Herhily’s book The Black Death and the Transformation of the West. Yes, what lay ahead was beyond the wildest dreams of the pre-plague peasantry, but the trail they blazed to their emancipation was pure capitalism. It was also pure growth-based economics. Can we have one without the other?

The state of feudal society in the 1340s

The 11th to 13th centuries had been a period of relative growth and prosperity in Europe. REF: W. Mark Ormrod (2000). “England: Edward II and Edward III”. In Jones, Michael (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 6, c.1300–c.1415. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-13905574-1. This may well have been climate related – it coincided with the Medieval Warm Period, which was now ending, to be replaced by the beginning of Little Ice Age – a name given to the next 500 years of global cooling, especially in the North Atlantic region. The trend of population growth was bucked by the Great Famine of 1315 to 1317, which affected the whole of northern Europe. In 1315 it rained throughout the spring and summer, grains did not ripen, straw and hay could not be cured, and salt for preserving meat could not be extracted from sea water without sunshine. Only the rich could afford stores of grain for long-term emergencies. Bad weather caused the crops to fail in 1316, and the situation was exacerbated by disease in cattle and sheep that caused a drastic fall in their numbers. The resulting hardship, which peaked in the summer of 1317, resulted in extreme levels of crime and disease. So much seed stock had been eaten that it took until 1325 for food production to return to pre-famine levels. The famine was devastating, but it was an accident waiting to happen. More people were living in Europe than it could comfortably support, especially in the towns. Estimates for death rates in France and England are about 10-15% of the population.When recovery came, it was half-hearted. The core of the problem was the feudal mode of food production, which was based around small peasant farms being worked with technology that was not developing. The only way to grow food production was to increase the area being worked, but that had long been subject to the law of diminishing returns. All the best land had been taken long ago, and further expansion was only possible into poor soils which offered poor returns for work. This meant the peasants struggled to even produce enough to feed themselves, which left less surplus available for sale. Studies based on Normandy [ref Herhily 36] show that as average production fell, so did the amount of rent it was possible for the feudal lords to extract from the peasants. This led to a “crisis of feudal rent” [same ref], forcing the lords to see alternative sources of income, which generally meant pillaging the peasantry and hiring themselves out as mercenaries, pressurising their overlords to wage war on their neighbours in the hope of making money out of plunder and ransoms.

For the 50-100 years before 1348 Europe had been overpopulated, and yet relative stability prevailed. High food costs and frequent famines did not cause a Malthusian collapse. In the words of historian David Herhily:

“The economy was saturated; nearly all available resources were committed to the effort of producing food, clothing and shelter needed to support the packed communities. Agriculture was mobilized for the production of cereals, the basic foodstuff, and cultivation had extended to the limits of the workable land. Undoubtedly, vast numbers of Europeans lived in deep deprivation, But despite misery and hunger, the pressure of human numbers went unrelieved. The civilisation that this economy supported, the civilisation of the Middle Ages, might have maintained itself for the indefinite future.”

Instead of a Malthusian reckoning, there was a Malthusian deadlock. This was the last time that European civilisation was sustainable, and it was sustainable only through human misery and hardship, and a socio-economic system which obstructed technological and ideological progress. There was no notable trend in scientific or technological improvement to break this deadlock. (From the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century by Robin Briggs):

“The Middle Ages had failed to find an answer to the problem of food supplies: agricultural and industrial techniques had not advanced fast enough to meet the demands made on them. This failure of medieval technology was not directly connected with medieval science, since the latter was largely a challenge to prevailing theology and philosophy, trying to deepen the understanding of God’s world. For most laymen, the primary application of science was astrology and other magical practices. People just did not appreciate how powerful science was destined to become in the future advancement of technology."

But this was all about to change. The Malthusian deadlock was about to be smashed apart by the deadliest pandemic in European history. The socio-economic system of the Middle Ages was about to be cleared away, a process that was pre-requisite for the emergence of civilisation as we know it.

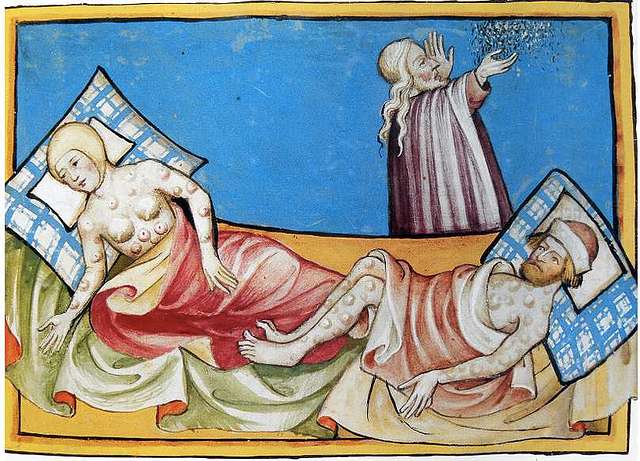

The Black Death (1346-1353)

It started somewhere in the East, and by the early 1340s it was moving westwards down the Silk Road. It moved slowly at first. Herhily 23 : “To spread widely and quickly, and to take on the proportions of a true pandemic, plague must cross water. Contact with water ignites its latent powers, like oil thrown upon a fire.”

In 1345-1346 the Black Sea port of Kaffa was besieged by a khan of the Golden Horde, and he had catapulted the bodies of plague victims over its walls. The infection caught hold, and from there it broke into the Meditteranean trading network. A characteristic pattern emerged, whereby the plague would take hold first in a port during the summer, then die down during winter, before raging again the following spring, both into the hinterland of the port and across the sea into new ports. In 1347 it infected Constantinople, Cairo, and Messina (Italy), and then swept through Greece, Lybia, Judea, and Syria. In 1348 it arrived in Florence, Marseilles and Barcelona, and first appeared in Britain, in Weymouth in Dorset. In 1349 it raged across Britain, and in the next three years it moved back eastwards, almost going full circle, reaching Kyiv in 1352. By the time the infection died down, something like 40% of the pre-plague population of Europe were dead.

Despite the unimaginable horror of living through it, the Black Death was arguably a prerequisite for the transformation of the West from medieval feudalism to modernity. The patterns in which society had been locked were blown apart, ready to be rebuilt with a very different structure. The world had not quite been turned upside-down, but it had been loosened from the restrictions that had previously prevented it from moving very much at all – for as long as anybody could remember, there had been an oversupply of peasant labour and a shortage of land, especially the good stuff. Now there was such an abundance of land that much of it could not be maintained, and a severe shortage of labour. The rural economy of Europe broke down almost completely, and towns and cities were largely deserted. All manner of posts in society went unfilled, and services unperformed. Domestic animals roamed untended. Even the poorest of the poor found well-paid work as grave-diggers. Many of them also suddenly found themselves financially able to afford an education, having inherited from victims of the plague. Physicians and clergy were in desperate demand, leading to a great deal of opportunity for people in the lower rungs of society who would normally have never had a chance to better themselves in this way. Women were provided with opportunities usually only open to men and people not belonging to guilds could perform services previously restricted to guild members.

These problems were aggravated by the plague’s tendency to hit hardest at people in their most productive years, while relatively sparing the young and the elderly. The professions therefore had to recruit aggressively, especially among the young. [Herhily: “Society tried to keep its occupational cadres constant in size, even though the total community and the pool of possible members were shrinking. The policy reflects in part social resistance to any disturbance or change, and in part too the premature deaths of old masters. But to enlist constant numbers out of a shrinking pool, the guild had to spread its net broadly and bring in new apprentices with no previous family connection to the trade…Probably in all occupations, the immediate post-plague period was an age of new men.” Religious orders had also fallen into decadence, the depletions in their ranks replaced with young men lacking the piety or training of those they were replacing. The quality of the product, in all spheres, was suffering, but resistance to change was being broken everywhere. An age of new people opens up the possibility of an age of new ideas.

But the primary reason for the change in situation was the freeing up of resources. Land previously used for grain production could now be used to raise animals, or even turned back into woodland. Mills that had been used for grinding grain could now be used to full cloth, operate bellows or saw wood. As the population shrank, possibilities opened up for diversification of the economy. People also saw their diet improve, as a wider variety of foodstuffs became available to a greater proportion of the population.

Matteo Villani: “The common people, by reason of the abundance and superfluity they found, would no longer work at their accustomed trades; they wanted the dearest and most delicate foods…while children and common women clad themselves in all the fair and costly garments of the illustrious who had died.”

Governments across Europe tried to legislate against this, attempting to regulate fashions, or the food permitted to be served at weddings, the number of people allowed to attend funerals. These laws, of course, did not work. The poor now had high wages, and they had no intention of allowing either the government or the church to prevent them from enjoying themselves while they could. This new economic power at the lowest levels of society drastically increased their bargaining power.

Villani again: “Serving girls and unskilled women with no experience in service and stable boys want at least 12 florins per year, and the most arrogant among them 18 or 24 florins per year, and so also nurses and minor artisans working with their hands want three times or nearly the usual pay, and labourers on the land all want oxen and all seed, and want to work the best lands, and to abandon all the others.”

Governments tried to cap wages too, as well as introducing price controls to stem the inevitable inflation. They even tried to insist workers accept any employment offered to them. All this achieved was social uprisings.

In towns, the decrease in available labour was accompanied by an increase in capital. This led directly to the purchase of better tools and machines, and provided a golden opportunity to anyone who could invent and produce labour-saving machinery. This was to prove crucial in the course of future events. The technological stagnation of the pre-plague period was over, and rapid progress was now being made. This period saw the invention or development of crossbows, guns, clocks and eyeglasses. Ship-building and navigation also made great advances – bigger ships that could be handled by smaller crews, and so remain longer at sea and take more direct routes. All this new economic activity led to an increase in business and financial services, such as maritime insurance. Most important of all was a revolution in the production of books. When labour is cheap, it is viable for scribes to produce hand-written books. It took until 1440 for the technology of printing with movable type to be perfected, but Gutenberg’s achievement was just the end of an intense period of experimentation that began in the wake of the Black Death. The books that were now available in large numbers and at low prices supplied a market of literate lay-men.

The universities were greatly affected. They were responsible for training doctors, lawyers and theologians. Enrolled students at Oxford declined from a pre-plague high of 30,000 to 6000 in the late fourteenth century. But increases in capital, especially from pious bequests, also led to the establishment of new colleges at existing universities and also to new universities, especially in continental Europe.

Herhily: “While it weakened the dominance of a few international centres, the proliferation of universities gave the new foundations much more of a national constituency than any school had shown before. This surely loosened the international cohesion of medieval culture and prepared the way for the theological schisms coming in, and even before, the Reformation. The plague helped to bring the age of cultural nationalism to Europe."

Medicine also began to change. The system of the four humours, which had dominated since antiquity, had no theory of infectivity, but the plague was obviously infectious. Confidence diminished in the knowledge of the ancients. Anatomical investigations took on a greater importance. Quarantine procedures were introduced in European ports for the first time.

Between 1347 and 1352 somewhere between one third and one half of the European population died. In some places the death toll was far higher. The feudal system was already decaying before the plague hit, and this was not the end of that system, but it was surely a devastating blow, and it helped to generate the circumstances that allowed the steady replacement of feudalism with capitalism.

It took until the 16th century for the population to recover to its pre-plague levels, by which time European society had been transformed from Christendom to early modernity.

Can we have capitalism without growth? I have no idea.